As the film required thousands of frames, printing them all would have resulted an ecological disaster. That’s why we connected to the device via network and extracted digital data from its internal memory. However, it turned out that not all copiers are capable to do this, and even if the analog picture seems to be OK, digital data may still be much worse. Another problem was depth of field. As we lighted the space over the copier, we imagined that the machine would be able to look as high as the scanners in general. It turned out that there are at least as many sensors in the copier market as in cameras, some sees higher, some sees just one centimeter. Of course, only A3 copiers could come into play, the A4 machines failed to show anything from our heroes.

As the film required thousands of frames, printing them all would have resulted an ecological disaster. That’s why we connected to the device via network and extracted digital data from its internal memory. However, it turned out that not all copiers are capable to do this, and even if the analog picture seems to be OK, digital data may still be much worse. Another problem was depth of field. As we lighted the space over the copier, we imagined that the machine would be able to look as high as the scanners in general. It turned out that there are at least as many sensors in the copier market as in cameras, some sees higher, some sees just one centimeter. Of course, only A3 copiers could come into play, the A4 machines failed to show anything from our heroes.

We have started to look for the suitable machine. It did not help that we couldn’t tell anyone our real goals, as nobody would have agreed to lend us the equipment. We tried to estimate its weight as we said: we are copying encyclopedias. For examining the depth of field, we took a measuring tape to each salon with us and we measured how long the sensor could look up.

We have started to look for the suitable machine. It did not help that we couldn’t tell anyone our real goals, as nobody would have agreed to lend us the equipment. We tried to estimate its weight as we said: we are copying encyclopedias. For examining the depth of field, we took a measuring tape to each salon with us and we measured how long the sensor could look up.

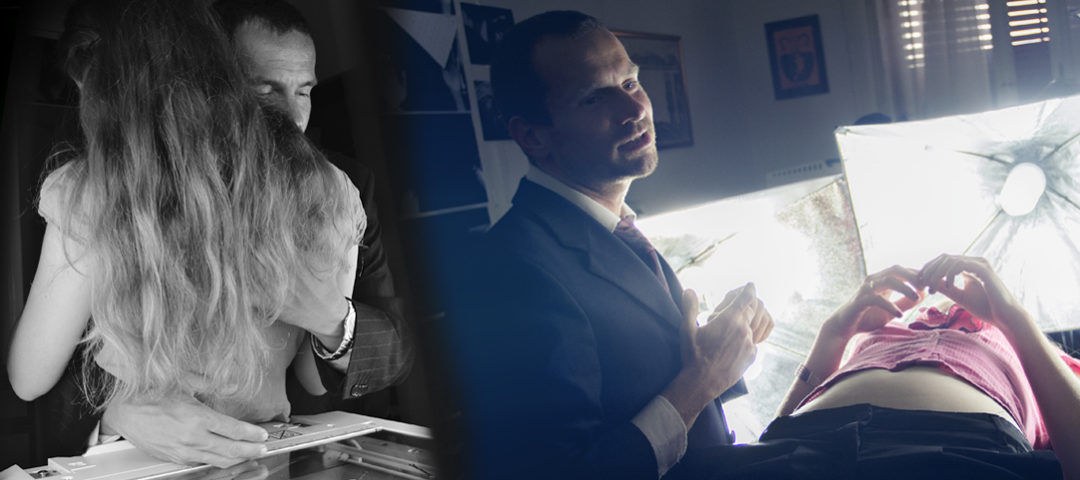

The forced break resulted in the expansion of the concept, and we welcomed a new crew member: Attila Simon’s acting skills had a great influence on me in the television where we worked together. Fortunately, he showed interest in our strange production. This inevitably widened the character of the man hero, and now we could show his face as well.

Principal photography of The Copyist took a month as we rented the copier for that long. 3 full days were with actors, obviously these were the hardest. From the top of the copier, all dispensers and covers have been removed to keep the mere glass. Although we did not want our actors to lay on the top completely, for safety reasons we structurally reinforced the copier at several points. After that the lighting came: the machine’s own light would never have been able to illuminate the entire space, so we packed as much lights around it as we could. The sensor, with such help, unleashed half a meter of playing area in height.

The shooting required great discipline from the actors. The screenplay was broken down into sections of 10 to 15 seconds, averaging 4-5 images. We first discussed and invented the movements, tested the situation, and lighted the scene. Then, for about 20 minutes, the actors re-played the 4-5 movements in question over and over again. In the beginning it meant that they were fozen in one position, and later they moved more and more, depending on where the scanning module itself was.

The shooting required great discipline from the actors. The screenplay was broken down into sections of 10 to 15 seconds, averaging 4-5 images. We first discussed and invented the movements, tested the situation, and lighted the scene. Then, for about 20 minutes, the actors re-played the 4-5 movements in question over and over again. In the beginning it meant that they were fozen in one position, and later they moved more and more, depending on where the scanning module itself was.

Leaning over the copier, it was impossible to determine which movement looked good: not only was it upside down, but as a result of scanning, what the actors could see had nothing to do with what the machine saw. All we could do was follow the plans. In about 20 minutes, we took enough pictures to draw our conclusions. Everyone was gathering around the computer and we downloaded the internal memory data. We drew the conclusions, refined our ideas, then came an other 20 minutes of shooting. With this working method, we were able to have a great deal of control over the images, all the hairs, all the slight distortions which we could manipulate with surprisingly high precision. During three shooting days, we recorded more than 5,000 copies of our actors, which became the spine of our movie.

Tamás Kőszegi

photos: Diána Nagy

You must be logged in to post a comment.